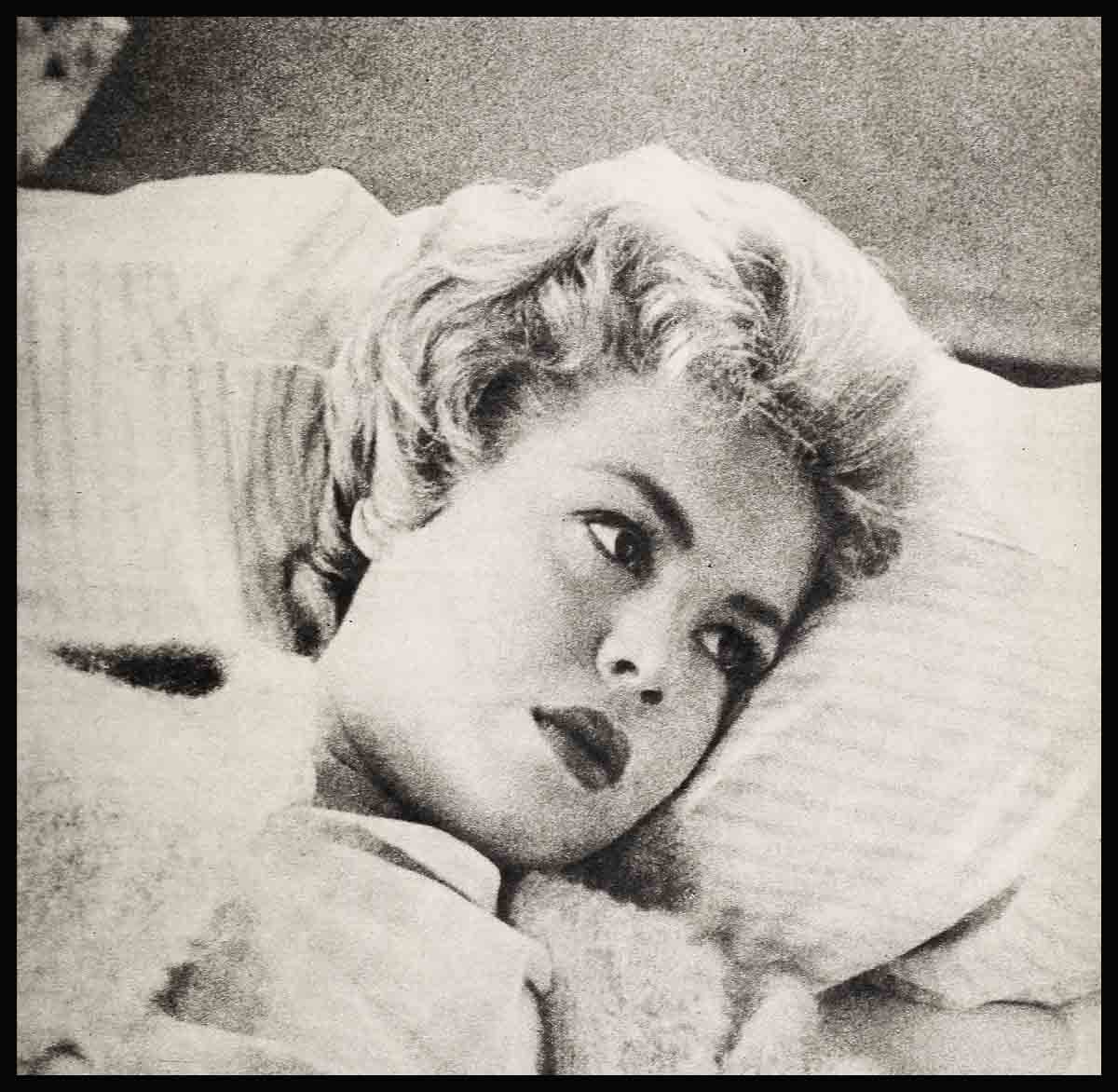

Vera Miles Says: “I’m Glad I Was Poor”

It’s an odd thing, but everyone reacts differently to poverty. With some people, early hurts built up an attitude of defeat and self-pity. In others, it propels them forward like a bullet. Vera Miles, who stars with Jimmy Stewart n “The F.B.I. Story,” was in the latter class.

Vera’s childhood was dogged with the kind of anxiety that hung over her like a grey fog. Instead of carefree school days, she knew the feeling of not belonging.

From the moment she was born, she was tragedy’s child. Only a few weeks before she came into the world, a sister had died under terrifying circumstances. The father, mother and four children had been cooped up in a little shack in the Panhandle section of Oklahoma. There was always tension and confusion in the crowded place, and one night the youngest daughter grabbed some pills which had been prescribed in small doses for the father, and gulped a handful like candy. That night, the child woke up screaming and died.

Shortly after this tragedy, when both parents were still numbed with despair and guilt, Vera was born. Instead of celebrating her birth with joy, her parents were torn with grief and doubts. The misunderstanding between her parents mounted, and when Vera was a year old, the marriage dissolved.

Family life, drab as it had been here became. even worse. They moved to Pratt, Kansas. where Vera’s mother got a job as a maid at the hotel and was gone from morning until midnight. Vera’s older sister, Thelma, took care of her and Vera remembers that she had to learn to be quiet and keep out of the way. Later, Thelma married when she was only 15 and left the dreary environment. Her two brothers went to a CCC camp. This. left little Vera with no one to watch after her at home, so her mother would often take her along when she went to work.

In order not to be a nuisance on the job, Vera had to learn to duck into closets not to be noticed. While other children her age were cuddled by parents, played with dolls and ran laughing and yelling in the outdoors, the little girl with the flaxen hair pulled tightly back in braids and with enormous brown eyes filling her thin face, pressed herself into a corner, never smiling, never talking. Once, a guest saw her and, feeling sorry for the child who never smiled, impulsively gave her a doll. It was the only doll Vera ever owned, and she’d hold it tightly, pressing upon it the love she couldn’t give to anyone else.

Her mother, for all her hours of hard work, earned only about $12 a week, and Vera learned how to be on her own. She’d come home to the single room from school and prepare dinner for herself. Food was usually beans and potatoes because they were filling and cheap. She wondered what it would be like to drink a whole glass of milk and when she would ever eat meat again, as she once had when the manager of the hotel treated her to dinner.

“I had no friends,” she recalls. “I, was so used to being by myself that I didn’t know how to enter a group and make small talk with them. I had been too used to day-dreaming, anyway, and I seemed to be far removed from everyone else. I was an outsider. Even though I was used to it, I felt miserable and lonely.”

In her make-believe world she dreamed of a time when she’d leave the shabby one-room flat and live in a sunny home with lots of rooms. She dreamed of having pretty clothes, plenty to eat, and someone who loved her.

But she knew that day-dreaming wasn’t enough. When she was only 11 she started to work in the hotel dining room with her mother. She thought it would be wonderful to wait on tables, because of the tips. But she was so shy she couldn’t talk to the customers, so she helped out by cleaning off the tables instead.

Because she had been so completely on her own ever since she was seven, Vera developed a strength within herself.

“Poverty and loneliness can be awful,” she says, “but I gained a lot of security within myself because of it. I knew, after a while, that no matter what happened I could take care of myself. Nothing would ever frighten me again because I could find the solution within myself.”

She did when she was 14. Her mother’s work as manager of the hotel’s coffee shop began to take her on travels, so it was decided that Vera would live with her grandmother in Wichita, Kansas.

Vera, who’d never learned how to make friends in her own home, found it even more terrifying being thrust into a new town. She retreated more and more into a shell, and was made ever more miserable because she and her grandmother didn’t see eye-to-eye.

“We were two generations apart,” Vera says. “We were like strangers, and we couldn’t live together.”

When Vera discovered that her grandmother could rent her room to a paying boarder, the situation became intolerable and Vera moved out. Instead of weeping over her unwanted position, she did something about it. She went to the Western Union offices, and by fibbing about her age, got a job working after school until midnight. Where to live? She talked the local “Y” into giving her a room and meals in exchange for working in the cafeteria at breakfast.

“I didn’t want to give up school,” she says. “I knew how important it was to a girl like myself. I had to have the schooling so that I could get a better job for myself later on. I had to think of making a living, so I took up typing and bookkeeping.”

For three years she continued in a rigorous groove, getting up at 5:30 to work at the Y, going to school until 3, then hopping a bus and working until midnight.

There was no time for boy friends or fun, no time for anything but work and school.

Then suddenly, the picture changed. Ironically, although she’d never been able to attend a school dance, she was named one of the queens of the Senior Prom.

This started her on a string-of beauty contests which ended by her being sent to Atlantic City as “Miss Kansas.”

But she wasn’t taking any of her good luck for granted. She asked for a leave of absence from her Western Union job. “I’ll need it when I come back,” she told her boss.

“I had no talent,” she recalls. “I couldn’t sing or dance or entertain like the others. I went because it was a free trip and I’d never had a trip like that before.”

The answer to her future seemed to come when she placed third and won a $2500 scholarship that would help her through college. She could see the end of poverty now. She’d study to become a school teacher.

But that’s not what life intended for her after all. Several movie talent scouts who flocked around the “Miss America” contest, noticed the aloof, blonde girl. Because she was still too shy to mingle with the other girls, Vera remained by herself. Scouts from three studios were struck by her seeming cool personality and compared her with Grace Kelly. They all offered her term contracts. “You have a patrician air,” one of the scouts told her. “You look like a debutante.” And Vera smiled.

Because she was actually frightened at the prospect of becoming an actress—a career she’d never dreamed of in her wildest fantasies—she couldn’t say a word. Mistaking the hesitation for reluctance, the RKO man tried to persuade her to accept. We’ll pay all expenses to Hollywood for yourself and your mother. We’ll do everything to make you happy.”

Who could turn down a free trip to Hollywood? Because her childhood had given her so little in common with young folks, she had no desire to throw herself into the social whirl that surrounds a beautiful new starlet in Hollywood. She took advantage of the acting lessons the studio offered its contract players and concentrated on improving herself as an actress, instead of making the glamour round with the eligibles. People at the studio wondered that such a beautiful girl was willing to give up the fun and excitement of Hollywood to study, but only Vera knew that the hurts of her childhood impelled her to keep going. Nothing else mattered except that she make something of herself.

However, her inexperience with young folks made her confuse the kindness of a boy she met at the studio with love. Bob Miles was working at the studio and was assigned to drive her around. Bob told her she was lovely and wonderful and that he loved her. For the first time in her life she discovered what it was to have someone around to care about her and impulsively she eloped with him.

Almost from the beginning she learned that the marriage wouldn’t work out. They were too young, for one thing, but because she knew the tragedy of divorce in her own home, she was determined to stick it out. Two little girls, Debbie, now 8, and Kelley, 6, were born.

She stuck doggedly to her marriage for six years, only because she dreaded a broken home. One day, she realized with a pang that the six could stretch into sixty unhappy years, so after talking it over, she and Miles agreed to separate.

Her career wasn’t doing well, either. Her contract at RKO had lapsed, and a term at 20th and Warner Bros. had also come and gone. Work was scanty and the old anxieties returned, but she wouldn’t be licked.

She had learned how to stand on her own two feet as a child, how to hold down two jobs and school work without cracking, so she knew in her heart that she could, somehow, take care of her little girls.

“That,” she says ruefully, “was one of the advantages that hard knocks gave me. I had developed a will like iron. I felt that I could get along. It was nothing for me to work 18 hours a day, and I could do it again if I had to.”

She managed to do the leads in many top TV shows, like “Schlitz Playhouse” and “Medic,” but the work was uneven. There was no false pride about her. She knew what it was to be hungry, and she was determined that her little girls would never wonder, as she once had, what it would be like to drink milk out of a glass like water. She was about to apply for a job at Western Union again, when she received a call to see John Ford, one of Hollywood’s biggest directors.

“Would you like to do a picture for me?” asked Mr. Ford.

“Work—for you?” she said weakly. “You mean it?”

“I do, and you will,” said Mr. Ford, bringing the interview to a pat conclusion. Later she learned that his wife had seen her on a TV show the night before and had told him, “This girl has character as well as beauty,” and John Ford, watching her, knew that he wanted her to play the spunky frontier girl opposite John Wayne in “The Searchers.”

Things happened fast after that. Alfred Hitchcock signed her to a five-year contact, and her future was as assured as though she’ bought a controlling interest in the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce.

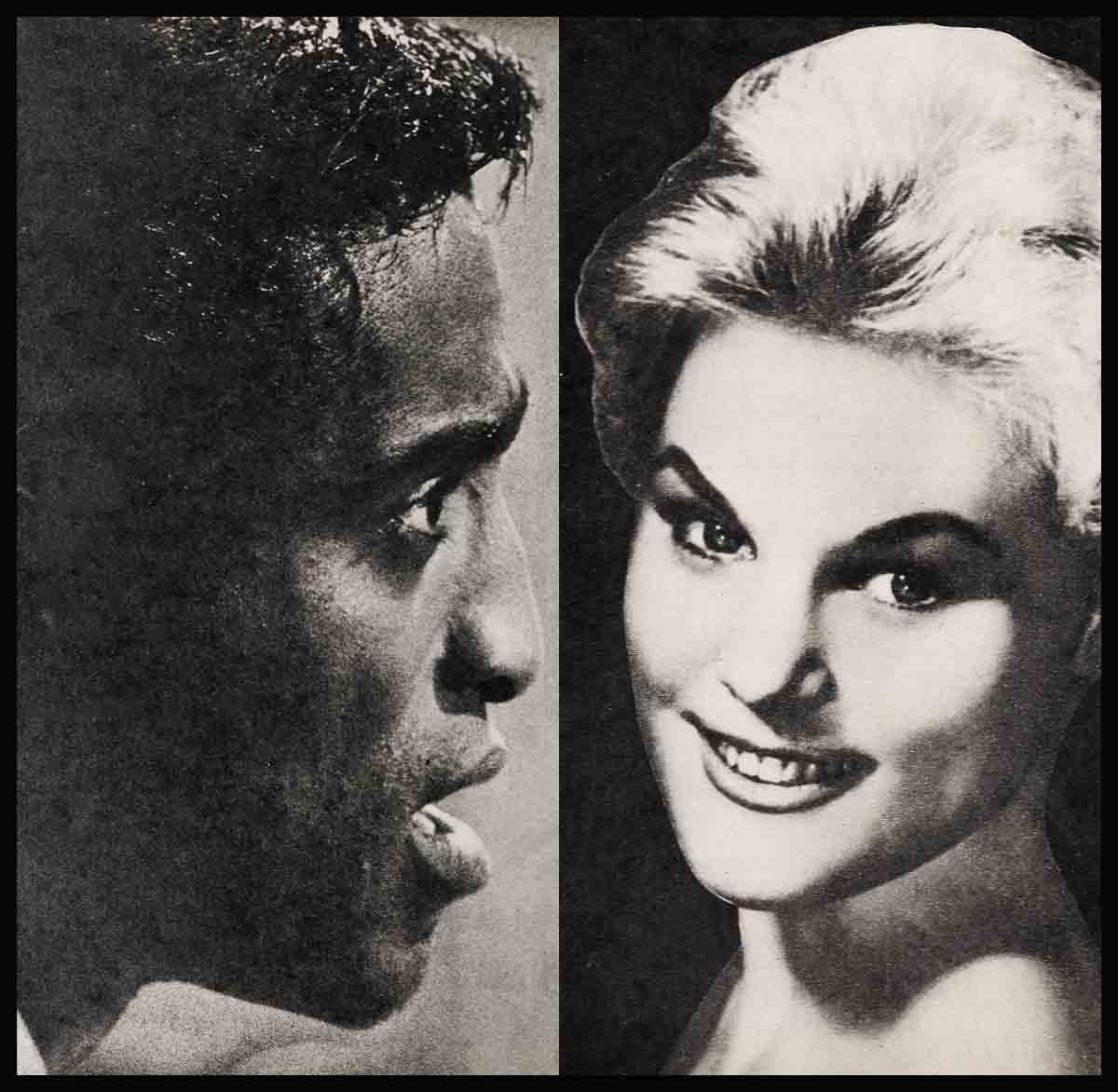

It’s logical that a girl who’s had to use her head all her life would still retain the habit of thinking sensibly, even though her life has turned glamourous. In April, 1956, she married Gordon Scott, the screen’s husky young “Tarzan.” She had met him when she was his leading lady, but she went with him for two years before she decided to marry him.

The impact of her parents’ tragic marriage and her own teenage mistake was so strong that she didn’t want to marry again until she was absolutely sure it was right.

It took Gordon two years to talk her into becoming his wife, even though she knew she was very much in love with him long before then.

Because her strongest obsession as a child was to get out of the drab flat she and her mother lived in, the first thing she and Gordon did was to buy the largest home they could afford in the Valley. It has 11 rooms and sits in the middle of a two-acre orchard. It was an old house that needed a lot of re-doing so they were able to pick it up at a steal. They didn’t throw their money around. Vera, who’d sewn her own dresses when she was nine, made up the draperies. Gordon, who’s a do-it-yourself man, worked on cabinets and helping the workmen knock out walls. Vera wants the rooms to be large and light, another throwback to the days when she vowed she’d get out of the hole in the wall.

Although she is small-boned and has Dresden doll features, she is as strong as a stevedore. The only quarrels she and Gordon have had have been over her tendency to haul furniture around while he is gone. When he comes home and sees the piano sitting where the sofa was in the morning, he tells Vera impatiently, “But, honey, that’s what I’m supposed to do around here. I’m the man in the family, remember. . . .”

And Vera laughs. “It’s that dreadful independence of mine,” she told me. “I’m so used to doing for myself, I still can’t get in the habit of asking anyone to do anything for me—not anything.”

Adding joy to her life was the birth last year of a son, Mike, who fills the house with laughter.

Although life is golden today, the past is always part of her. And for that she’s glad. Poverty and worry gave her the driving power to make her life a success. Early hardships etched character in that beautiful, young face of hers. Beauties are a dime a dozen in Hollywood. With Vera it’s more than the perfection of her features, the sex appeal in her figure. It’s the depth and force in her personality that makes her stand out in a field rampant with beauties.

All those childhood fears are gone now, as though they were ghosts made of smoke. But they helped make her the woman she is today.

THE END

—BY AMY FRANCIS

It is a quote. SCREENLAND MAGAZINE MAY 1959

No Comments